Julia testing the waters

Split Lip Press / Magazine is excited for Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach and her new chapbook The Bear Who Ate the Stars, a Split Lip Press release forthcoming on November 1st, 2014. We thought it would be fun to place this amazing poet under the microscope and discuss poetry’s role in her life, her creative process and her thoughts on poetry as a subject for study in higher academia. What we discovered was fascinating and, at times, a little surprising. We appreciate her candid replies to each question and are happy to share a little of her world with you.

I have never met a poet who knew they wanted to be a poet prior to writing poetry. How did poetry enter your world? Did you choose it? Did it choose you?

I was lucky to grow up surrounded by the music of poetry. For bedtime stories, my parents would read me Pushkin’s epic rhymed and metered fairy-tales or recite lyrics by Esenin and Blok. After we emigrated from Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine, and I began attending school in the US, to help me maintain my Russian, my parents would assign classical poems for me to memorize. I can never thank them enough for raising me with poetry in my mouth and in my ears. I guess you could say I got a taste for it from an early age and was simply hooked on the lyric. I would have to say that I neither chose poetry nor did it choose me, but rather, we fortunately found each other, and while I’m sure that poetry could easily survive without me, I would be helpless without it. It is the way I learn to understand myself. The way I try to make sense of the world. The way I hear and speak stories. And the way I hope, in some small way, to inspire change.

One can approach writing poetry in a number of ways. How would you describe your creative process? What triggers your ideas? How do you begin? How do you know the poem is complete? What happens in between?

My approach to writing changes by the day, if not by the hour.

Sometimes, I have a particular narrative or idea that I want to explore in a poem, and when that’s the case, I usually do some preliminary research (anywhere from calling my grandmother to Google to ordering books from university libraries) and then get some initial thoughts down. Usually, when I know what I want to write about, it takes me much longer to actually write it. And most often, even when I think I know what I want to say, the poem can take me elsewhere all together.

On rare occasions, a line or image does strike in the middle of the night and I search frantically for my phone to type it in. And yes, I almost always type when I write. When I use pen and paper, it feels like my hands can’t keep up with my thoughts—I’m a believer in getting more lines on the page and then paring down in revision.

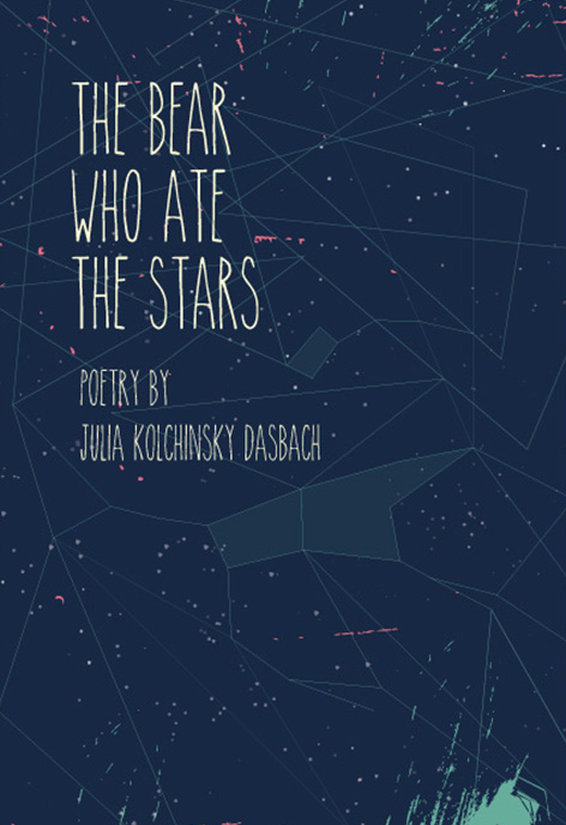

Julia’s forthcoming Split Lip Press Release due out November 1st — CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFO!

Most days, though, I come to the screen without anything particular in mind just to write, and lately I’ve been good about sitting down for a few hours everyday—it has made a huge difference, let me tell you. I like to use images, news stories, other poems, and even prompts for inspiration, and often this kind of forced writing leads me to some of the most interesting discoveries.

MFA and PhD programs for creative writing are a delicate subject matter with many proponents and just as many opponents. Given you’ve had the experience of studying your craft at a graduate level, how would you defend one’s decision to earn an MFA or PhD in poetry or any of the arts for that matter?

While I can’t speak to the creative writing Ph.D., given that I ultimately decided to go for a Comparative Literature doctorate, I can say that the MFA was by far the most enriching experience for my writing and my identity as a writer. It is a time to be fully immersed in your work and the work of those who inspire you. A time dedicated solely to writing and reading. A time to hone your craft, develop a language for talking about it, and learn even more through the practice of teaching. Creative writing programs are also a way of establishing a community of writers and mentors with whom you will be able to exchange work and discuss poetry for years to come.

Overall, the MFA is something I would encourage all writers to strongly consider, while understanding that this kind of head underwater writing experience is not conducive for everyone’s process. It is intense. It is all-in. It is a grueling writing boot camp that tears creative muscles, but ultimately, helps them grow back stronger, more powerful, and better prepared for the literary world.

For more on my particular experience at the University of Oregon, check out this 2012 LitBridge interview I did during third-year in the program.

Like playing hand drums or painting abstract art, a lot of people believe they can write poetry without much practice. In your opinion, what qualifies one to be a poet? What do you look for in another’s poetry to assess its merit?

I don’t think any artist is ever “qualified” to practice his or her craft, and I’m certainly in no position to judge. In fact, I’m not sure I’m really “qualified” to write poetry, but I simply can’t help it. When I sit down to write just about anything, a poem is bound to come out. I’ve been fortunate to be able to dedicate myself to the study of poetic craft and composition, and to gain a small but loyal readership, but I think this makes me lucky rather than “qualified.”

When it comes to the arts, tastes are so subjective. I grew up with the saying, “на вкус и цвет товарища нет,” [transliteration: na vkus I tzvet, tavarishya net] which means, roughly, “In matters of flavor and color, there are no friends.” Of course, it sounds much catchier in Russian, but the basic gist is: to each his or her own. The poetry I love most is very musically driven, and even though I for the most part write free verse, I grew up on traditional metered and rhymed Russian poets, like Pushkin, Esenin, and Mandelstam, so lyricism, continues to be something I look for and greatly admire when reading poetry. I am also drawn to a careful handling of language, rich with precise and palpable images that leave me returning to the works again and again.

I must also confess that “good” poetry, and poetry I simply love, is not always one and the same. There are many poets in whose work I see great artistic merit (be it for the rhetoric, music, imagery, etc.) but that doesn’t necessarily mean I will want to read and reread their poems. Guilty pleasure poetry that sometimes lodges itself like a bone in throat, is just as important to enjoy as the infamous work of American and international greats.

In a recent interview with Philip Levine, now in his 80s, he was asked what he thought to be the greatest lesson he had learned through the course of his career. His answer was along the lines of “I learned how to say no to a poem and move on to another.” As an experienced poet, what has been the greatest lesson you’ve learned so far?

This is a hard question because I still feel like I have so much to learn, but I guess if I had to choose a single lesson, it would have to be something I heard in one of my MFA poetry workshops regarding the revision process.

The professor said something to the effect of: sometimes, the line or moment in the poem with which you are most in love, is the very one that is most in need of cutting.

Writing the initial draft is often the easy part, but revising it to find the real poem lurking inside can be extremely difficult. Too often, we become enamored—in a blind-love sort of way—with our own words. This prevents us from seeing how the poem functions as a whole. That’s why, letting go of these lines or moments, can be a way of lifting the starry-eyed dream veil of infatuation that we’ve cast over the poem, and seeing instead, what else is at work. Perhaps, ultimately, the line or moment will find its way back to the poem, but as an exercise, we should have the courage to excise that heart which draws us most, if only to understand why we were drawn to it and see the lyric body left behind in its absence.

And to wrap up, how about I ask the quintessential question when interviewing an artist. What kind of advice would you give a new poet looking to make his or her way into the literary scene?

I wish I knew such good advice. If I did, I would have taken it by now! But in all seriousness, the most important thing I’d say is be true to your own poetic voice and vision. And if you aren’t sure what that is yet, then just keep searching, keep reading, keep writing, and don’t let anyone else define who you are as an artist.

As writers, the plague of self-doubt and anxiety is inescapable—if anyone knows a magic cure for this, I’m all-ears. All we can do is stand behind our words, always hoping that someone overhears them.