Interview by Michael Soloway

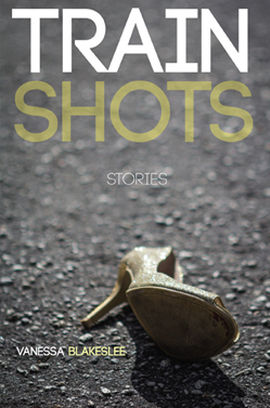

A single mother rents a fundamentalist preacher’s carriage house. A pop star contemplates suicide in the hotel room where Janis Joplin died. A philandering ex-pat doctor gets hooked on morphine while reeling from his wife’s death. And in the title story, a train engineer, after running over a young girl on his tracks, grapples with the pervasive question—what propels a life toward such a disastrous end? Being released by Burrow Press in March, this is just a sample of author Vanessa Blakeslee’s debut short story collection, Train Shots.

Although born and raised in northeastern Pennsylvania, Vanessa is a longtime resident of Maitland, Florida, and earned her MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Vanessa’s work has appeared in The Southern Review, Green Mountains Review, The Paris Review Daily, The Globe and Mail, Kenyon Review Online, and right here at Split Lip Magazine, among other publications. Winner of the inaugural Bosque Fiction Prize, she has also been awarded grants and residencies from Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, The Banff Centre, Ledig House, the Ragdale Foundation, and in 2013 received the Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature from the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs. I had an opportunity to speak with Vanessa about Train Shots right before the Holidays. And her humility, insight, grace, and pure joy of literary technique are just as lovely as her prose.

Thank you for talking to Split Lip today, Vanessa. And congratulations on Train Shots. It’s an amazing collection of work.

Thank you. It’s my pleasure. I appreciate the opportunity to chat.

Vanessa, I noticed all of the stories in Train Shots first appeared in various literary magazines, some even received awards. That said, how did Train Shots come into being? Did you set out to publish a short story compilation as you were writing or did someone approach you with the idea?

A little bit of both. I had been putting together a collection, putting together different stories, playing with the order and sending the manuscript to small press contests for a few years. It had placed a few times as a finalist at a couple of them but I was really getting tired of doing that and the fees were adding up as well. Then, I was fortunate enough to be approached by Ryan Rivas at Burrow Press. I had been doing a blog for them, a craft blog for the Burrow Press Review for about a year and I got to know Ryan. I guess he got to know me as someone who turned in blog posts pretty regularly, saw me as a diligent worker and knew that my stories were continuing to get published. It coincided with Burrow Press wanting to launch this short story imprint that they’ve had their eye on doing for a while. He approached me. He read the manuscript, the core of the manuscript. We talked and switched out stories. And decided that it would be called Train Shots. I had different variations of what it would be called.

Vanessa Blakeslee

You bring up an interesting point. Who decides the order of the stories in a compilation of short stories such as Train Shots? The publisher? The editor? Yourself?

I really am grateful to my editor for helping me out. It really was a conversation back and forth. I tried on my own to get the order right, but I think as writers, especially when you’re working on stories over a period of a few years, you can get too close to them or can’t see them as an outside person can. I was just so grateful to Ryan, my editor, when he came up with a “playlist.” He said he sees collections as albums. And I liked that analogy a lot. I think it’s very apt. It’s like a music album. You want the stories to speak to each other in certain ways. You don’t want to strike the same chord too often. Certainly there were stories I had that were perfectly good stories, but we ended up switching them out. Maybe one was too similar to another. Ultimately, I just found the analogy so helpful. I really appreciate someone being able to look at your work and being to say “yes” these go together and these are for another book.

I’m from Florida. Born in Ft. Lauderdale, raised in West Palm Beach, went to Florida State in Tallahassee. Because of this, many of your locations really resonate with me personally. How large a part, or character, does setting play in your stories? For example, Costa Rica makes an appearance in two of your stories. Do you believe setting can shape a story or simply support it?

I think in many ways it has to shape a story—definitely in terms of character and situation, because I see them as rising out of the setting. Then you might ask yourself, “could this story take place anywhere else?” And even if the answer is “yes,” the story would be different, because the place would be different and what the characters would be dealing with would change, even the climate. I’m thinking in particular of the Costa Rica stories. The story with the dogs, the stolen dogs—“Welcome, Lost Dogs.” Could that story take place in Florida or the United States for that matter? I don’t think it could. We don’t have the same relationship with street dogs. We don’t have that same element here. Not that we don’t have stray dogs, but it’s the way that street dogs are integrated into the neighborhoods in Latin American countries that is very different than how it is here. That was a story that entirely grew out of that place completely. Whereas the story about the philandering doctor, “Hospice of the au Pair,” I still think of as a very ex-pat rooted story. But, in contrast, it could have taken place in Florida or someplace Stateside. It wouldn’t necessarily have to take place in that location. Setting or location might also just depend on what the conflict situation is between the characters.

In “Clock In,” I love your voice and use of second person. In many of the scenes, I feel as though the narrator has a handheld camera and we’re watching the action through a lens. It’s quite unique and very personal. How did you come to the decision to write the story in this way?

That story is a great example of spontaneity and what can happen when you’re given a writing exercise. Because it was a writing exercise—to write something in the second person with a set of instructions—to instruct someone on how to do something, it was interesting to see how just following those instructions could create a piece. It opens with the task of explaining to someone how to use a restaurant computer system. When I just followed that, it unfolded into talking about the characters, and then the characters became the conflicts, what was going on with the characters. The story, in a really small amount of space, tells the story of this restaurant, and the tensions between the different players on the staff. What was happening with the staff? So, that was entirely unplanned. I’m really happy to have gotten that exercise. I don’t know if I would have ever thought to write “Clock In” without it. I’m sure I wouldn’t have actually, that the idea would have just come to me to write it. It was really just a happy accident. In fact, it’s the oldest piece in the book. I don’t typically write flash fiction, so I didn’t know if it would fit, or where, but it ended up being the perfect opening to the collection. And that piece was actually almost lost. I didn’t even have it anymore. My younger sister had it on her computer. For some reason I thought it was a fun little piece and I sent it to her years ago. She had it saved in her Gmail account, and during the process she said to me, “don’t you remember that great little piece you wrote about the restaurant?” So, she emailed it to me. If she hadn’t, it would have been lost in the oblivion of writing exercises.

Many of the characters throughout Train Shots have vices, illness and/or addictions: alcohol abuse, drugs, juvenile delinquency, mental illness, marital problems, a woman’s sexual abuse of minors disguised as “appropriate” because of loneliness and passion, smokers with one lung who would rather die having enjoyed life than quit, obsession with money, and the pursuit of perfection. Even in the story “Barbecue Rabbit,” the rabbit “has got a bad eye.” Is this a coincidence or is addiction a fatal flaw you consciously choose when you write?

I guess I’m fascinated by what pitfalls people fall into. Oftentimes it is addiction, but yet I’m aware that there are many stories about addiction out there. So, if I’m curious about morphine addiction in the case of the doctor in “Hospice of the au Pair,” I asked myself, “How can I put some kind of original twist on this scenario?” I also write a lot from stories and anecdotes from people in real life. I knew a girl that had dated a morphine-addicted doctor years and years ago and that stuck me. So when I set about to write that story, I brought in that element. I thought why not make him a doctor, so that we just don’t have a typical “junkie.” In the story, “Barbecue Rabbit” the father’s character, who was caught with the meth lab, I based on an uncle of mine who had gotten busted for the same offense. Relatives can provide an awful lot of inspiration. So, I basically took his back-story and this troubled teenager, and thought about the type of parents he might have. So, yes, I’m intrigued by characters and people who battle those demons, but I’m always looking for what kind of spin I can put on characterization to make it fresh. So I don’t feel like I’m writing the typical. You always want to stay away from stereotype. I usually find two or three different elements, composites that I can mix together to make character traits completely fictional.

In the story, “Ask Jesus,” with regards to a Jesus costume, you write: “He’s the super hero of the Bible Belt.” That’s hysterical to me. And there are other lines just as humorous. You manage to balance serious subjects—the collapse and possible end of a marriage—with subtle humor. Do you find this to be your strength? Does this come naturally to you or do you have some inspirational authors that have helped shape your voice and style?

You know the whole humor element has really taken me by surprise. It’s not something that I sit down to do. In the case of “Ask Jesus,” it arose out of crafting the situation and having it come to life. I feel like humor, and especially dark humor, is a mechanism, a response to a really stark situation. The humor needs that situation to bounce off of or arise from. I guess it’s just happened naturally. I haven’t consciously modeled my writing from anyone. Although at the time I wrote “Ask Jesus,” I was reading a lot of Barry Hannah and Padgett Powell—some people who are kind of “out there.” But I can’t say that I was actually studying them that closely to say that I was actually trying to add humor. But when you read other people they can certainly influence you.

In “Welcome, Lost Dogs” you have what I like to call “explicit imagery,” and so many poetic lines, such as, “A green gringo with palm trees in his eyes.” “…ceaseless rattling winds that sounded like my heart.” “…another person caught between countries.” This story in particular feels like a departure from the others and takes on a completely different voice. You’ve created such tension in this story specifically. One line in particular struck me: “Starving dogs will eat anything.” Is that the main point of the story? That even when the ex-husband is driving both characters through the murderous streets of Alajuelita, and we know, because it’s a flashback, that the protagonist makes it out alive, there’s still a palpable anxiety you create. It’s so real; so authentic. How much of that story, if any, is autobiographical?

I think it is [“Starving dogs will eat anything.”] a kind of thematic line for that story and the desperation of what any creature, including humans, can be pushed to perhaps—as uncomfortable as that thought may be. We don’t like to think of ourselves in situations so dire that we’d be eating anything, including perhaps each other. (No, I’m not into zombies.) In this story, there are also elements that really are autobiographical. It’s interesting that you honed in on the detour that the couple ends up taking in the slum, because that actually did happen to my ex-boyfriend and me in Costa Rica. We had left a friend’s house one night in the good part of town and we made a right instead of a left on this back road and we ended up in this barrio. I pretty much described that exactly from life. And it just so happened that it fit into the back-story. But you have to be careful in fiction. There are many things that happen to you that you wish you could put into stories, but is it warranted just because it was a harrowing experience that happened to you? But that one did fit; it fit the mood of the story and sensibility of the piece. But, yes, it was quite autobiographical. I spent about six to eight months in Costa Rica in 2008. I was back and forth between there and Florida. I had never been to Nicaragua, but I used what some neighbors of ours, some fellow Americans ex-pats who had a farm in Nicaragua, had told us. So I took some tidbits from them. The scene where the males are stealing the wood, and the wife’s confrontation with them, and the peasants eventually taking the wood, was an oral anecdote that our neighbors shared. Also, the hurt dog that was recovering from a broken leg, that was a story from some other neighbors of ours who had rescued a dog on the side of the road. I just cobbled things together I guess, and there are all these dog stories in Costa Rica. Because there are dogs everywhere. Whether they’ve adopted stray dogs into their homes or the strays are just part of the neighborhood, there are all these stories about dogs. That’s how that narrative came together. It was very much a story where the images lead me forward—it was very image driven as I was writing it. I started with the dogs and that lead to other “episodes.”

In “Barbecue Rabbit” you present a female protagonist who is in constant fear, always nervous, and who must deal with weapons and show strength. There is an apparent void of a vibrant, hopeful male presence. Is this a constant theme in your fiction? Would you classify your stories as small acts of a modern form of feminism?

I’m definitely one who’s interested in presenting stories about strong females. In “Barbecue Rabbit,” that particular protagonist is shouldering the task of raising a troubled son. I definitely don’t see her as a victim. She takes some active steps to get him help. But I guess I am interested in women who stand up and talk back and are not victims of their situation. I feel that can be true in “Don’t Forget the Beignets” as well. Where this man the protagonist has been relying upon cons her and ends up in jail. From there, she sets toward straightening her life out. I think it’s pretty apparent by the end of that story that they’ll be parting ways and that their time together is over. She’ll fend for herself and she’ll be fine. She’s writing this book and she’ll probably publish it and be just fine. Also, Margot in “The Lung” is definitely meant to be a pretty tough character who doesn’t take any BS from the male speaker and pushes him toward his change. And the protagonist of the dog story is very strong as well.

Also, I love the scene where Ethan’s bangs are hiding his tears; that his mother is too scared to take him to the barber for fear he’ll grab the scissors, which foreshadows the ending. Where do these images and endings come from?

For me, it’s putting myself in the character’s shoes and fully into the situation. Just imagining naturally what the details of that are, because I don’t have a teenage son. I don’t have any children. So, I just put myself there. It comes to me and feels natural—feels inevitable. In “Barbecue Rabbit,” I’m trying to give the reader a glimpse into her life. I guess I’m always trying to do that. In a short story, you have a very limited amount of space to do that—to provide those glimpses into a deeper world. Perhaps, there’s even a certain amount of pressure that drives you to write precise images and insights.

In “Uninvited Guests,” I love the symbolism and imagery of a Reverend having, “A statue of an angel kneeling in prayer tilted on shaded, uneven ground.” Do these kinds of images appear in first drafts or do you mine them later, as the story is revised and certain thematic threads present themselves?

Sometimes, of course, there are certain initial images you’re working with. This particular story was based on this funny house, just this interesting property—overgrown yard and yappy little dog and the cars with the Bible sayings on the license plates that were just a few streets down from here. I literally wrote a story about the house and the people who I imagined might be living there. And then what kind of conflict situation this older couple might run into and who they would be in conflict with. But definitely that story, as you said, was mined for imagery. I had the initial imagery of the angel statue, but I worked to make the angel statue more precise. For example, adding that it was standing on uneven ground. But it applies to the characters, too. At first pass, I felt like the Reverend was too stereotypical of a Reverend. I really worked to make the characters less stereotypical. I think that’s why I gave the cousin, as he drove up, an oversized redneck van but that he was listening to reggae. I worked to make that world a little bit off or uneven. So you don’t just have the redneck drive up with country music blasting. Pushing myself in that direction gives you a more accurate view. That’s why you have to “draft.” Because that’s what you may tend to reach for initially—the easier clichéd images. You have to mine. Mining is a good word.

“Don’t Forget the Beignets” has even more symbolism. I love the correlation between Andrew Jackson that you make and the protagonist’s recently arrested boyfriend on securities fraud. Later, in a restaurant with the protagonist’s cousin, a twenty-dollar bill, or “Andrew Jackson,” is slid over on a silver tray. Do you find these unique threads that bind your stories together or do they find you?

I call them image patterns. I studied under Douglas Glover, a Canadian author, and he talks extensively about image patterns—when you take an image, load it with meaning, then repeat it elsewhere. A lot of times these can crop up in the initial drafting. In the case of Andrew Jackson, because the story takes place in New Orleans, that statue is part of the setting, and an iconic symbol of the French Quarter. So, I had the protagonist go there. And then because the story also deals with fraud and Jackson happens to be on money, it’s kind of a readily available and believable image that could be worked back in quite naturally into the story—that she’s been conned by her partner, and the stakes are raised by what’s she going to do. There was also the idea of New Orleans as a place of deception and long history and criminal past, a colorful one. Similarly with the beignets, I don’t think I set out for her to bring them into the prison. But she had visited that place before and the beignets became a good prop.

In “Princess of Pop” you have a seamless and natural way of juxtaposing dreamlike, warm, beautiful childlike imagery with shockingly real, graphic scenes. Your opening paragraph references a child’s swing and floating off into the clouds, alongside quail hunting and the bloodied feathers in the back of a pickup truck. In this instance, were you commenting on the fine line between life and death?

In my stories I do tend to fixate on life and death and those high stakes. Maybe, for one, it’s the form. You have such a short amount of time to decide what really matters. You really have to grab the reader’s attention and sustain it. I tend to push myself to think about the great subjects, like love and death. I feel like in “Princess of Pop” it grows out of the protagonist’s point of view and where she is—very, very depressed, moving toward suicide. Her childhood has been so tarnished, but yet like anyone else she’s grasping for those idyllic moments. But she doesn’t really have any. They’re ruined for her. As a child star, even her brief time on the swing was cut short by the hunting. And her times as a teenager, which were some probably happy times, being in the “Mickey Mouse Club” were cut short by her mom having an affair with the manager and being whisked off to some other location. Or the brief time she was in regular school being cut short and this fantasy of the brown-haired girl she hangs out with, which is a projection of herself of course. All of that just grew out of that character’s psyche. I would guess that I write about these subjects often. I guess that’s just something I’m fixated on. If it’s not love or death, it’s got to be about being on the edge or relationships that are fragile.

That brings me to the title story, “Train Shots.” This story grabs you from the opening. I know people must be struck by trains more often than we think, but you manage to put the reader there, in a situation none of us have probably ever encountered or ever will. The motion of the story is slow. This is not to say the story itself is slow or boring. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. I find the pace sometimes appears to mimic the seemingly tired train engineer, who has hit and killed his share of animals, and now his third person in four months. Is that writing deliberate?

I did intend the story to be kind of a quiet story. The conflict is obviously manifested externally by the engineer hitting this latest woman with the train, but more so about this lone man grappling with the culmination of what he’s done, the perils of this job, and how he must reckon with that. I knew that not much would really happen action-wise, once he hit the woman, so I just wanted to see what he would do stuck for twenty-four hours overnight in this town, with the train right there—who he would meet and watching him quietly unravel as he ends up at the bar and getting drunk.

Was there purpose in naming the protagonist P.T.? That we only learn his initials and never his full name?

I’d read somewhere about engineers and train employee culture that initialed names or nicknames were popular. I can’t remember exactly why I named him P.T. Maybe I just didn’t want the character to be P.J. But I did read that somewhere. I don’t know how true it is. But I went with it. It’s pretty unusual. I don’t have any other stories that use initials like that. I thought, why not go with it? Something different. I definitely did a little research into that “culture” though.

Later in the story we find out what “train shot” really means. At this bar along the tracks, patrons buy tequila shots every time a train roars past. How did you come up with this? It’s pure genius.

Well, it’s because I actually worked at that said bar. I don’t know if it’s still open in town. In the early 2000s, I was a waitress and a bartender at this crazy, “Coyote Ugly” kind of Florida dive bar, a Tex-Mex joint that did a hell of a business near the train tracks in Winter Park. That would be our drink special—the train would go by and the bartender would clang his bell and we had to go up to all our customers and ask, “Train shots! Want a train shot? Train shots are two dollars.” So that was my life for a long, long time, these train shots. Occasionally we had some calamities with the trains. Nobody when I was working trying to kill themselves, but we did have various cars get stuck on the tracks. People turning in at night thinking there was a road there; the train tracks being dark. So, there were a few hairy times like that when the police had to come. But that’s where that came from. It just became one of those things I didn’t think I was going to write about but became inevitable, when the conflict situation came to me. And that conflict situation was an anecdote I heard at a dinner when some people were talking about this woman who was dating an engineer. She said, “Oh, he’s been having a hard time…his train has been having a lot of suicides lately.” That was the little spark. It’s something we lay people just don’t think about. So, when I set about to write the story I set it in Winter Park, because the train comes right through here. It’s a big part of our life here, so I thought of where he was going to go to get drunk—well, he has to go to the bar with the train shots. That has to be in his face again. There’s no escape. Even when he tries to escape he doesn’t, because the train shots are put in front of him.

How did that become the title story then?

Just as the opening story, “Clock In,” is flash fiction and has this brevity and is literally about opening the screen and giving a new employee a tour of the computer and the restaurant, it seemed like a natural opening. The same way, “Train Shots” made sense as an ending. Maybe because it is a quieter story, but also because it encapsulates such a double meaning—it’s literally the shots he’s taking but can also be like the collection itself, and my editor agreed, as the shots you see outside a train window, if you think of the book as a journey. And the book does cover a lot of locations. I think we both saw that double meaning wash back over the whole thing. And a lot of the themes planted earlier are touched on again—there’s a sort of echo that feeds into that story and the darker sides of life.

What about your editing process and thoughts on revision? Can you tell our readers a little about your personal style?

Many of the stories in this book began at Vermont College in the MFA Program. Some of them were part of my thesis and some were not, and I picked them up after I graduated. For some of them I had instructor/professorial feedback. But as they were published, I had input from journal editors. So, I had that layer of input, especially in the case of “Welcome, Lost Dogs.” I submitted it to The Southern Review. They initially passed on the first draft. But they gave me some comments and invited me to resubmit if I did a rewrite. So I did that. I got the comments back from them and really worked hard on it. I resubmitted it and they took it. So, that went through some extensive revision to get it where it had to be. And they really rarely do that. So, I had that level of editorial input at the literary magazine level. And then some of them I revised with my editor as we were putting the collection together. Some of them went through quite a bit of change. “The Sponge Diver” we changed quite considerably. Beefing up the whole scene of him making the protagonist stand in the shower with a poncho on. We thought that was a necessary moment to push the humor. That wasn’t part of the story that was originally published in the online journal. But that’s where the opportunity lies when you go to put stories together as part of a book—how to ramp up parts of stories, even if they were published before. You don’t want missed opportunities. Just take a closer look and decide where to tweak and where to change things.

Author Nigel Watts talks about an 8-point narrative arc, from stasis to a new or altered stasis. Do you believe that the short story must follow a strict structure such as this or is there room for open endings, in which much is left for the imagination?

I think for me there does have to be some kind of reversal—an oscillation between connection and disconnection. By the end, things have to have been changed up. I think you have to have that. As far as the form, I’m definitely interested in exploring. Because I’m becoming more interested in what I see as the two different branches of short story telling—stories that harken back to Poe and that speculative haunting, or going for that singular effect versus those stories rooted in social realism, like an Alice Munro story, which traditionally might follow the Chekhov or Joycean depiction of daily life. I’m interested in both of those. Maybe certain elements of one can be borrowed and inserted into the other. I don’t know. We’ll find out.

You graduated with your MFA in Writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. How did that experience help your writing and writing life? To aspiring authors reading this interview, would you recommend an MA or MFA program? I know success is never guaranteed, but in your opinion, where do you think you’d be without the added education and support of a built-in writing community?

I’d be struggling without it. Struggling in the sense that I knew I wanted to take my writing to the next level. I knew I didn’t really have as firm a grasp on form and craft and tradition as I needed. And I was looking to acquire a skill set that I could apply to my writing, and to come out of a program with a set of stories that could possibly become my first book. And that’s what I set out to do and that’s what happened. I really believe in the intense study that you do in a low residency style program. For me, an MFA was invaluable because it teaches you how to write and work on deadlines on your own, and master that over two years. After two years of turning in packets, you develop a habit and learn how to push yourself to produce more material and revise that material. And you really get a sense of what’s worth working on and what’s not; you gain a certain perspective. I would not be the writer I am today without the Vermont program. I’m very grateful for it.

And lastly, what are you currently working on? Do you have any interest in an extended narrative arc, perhaps to one of your short stories or a novel about a completely different subject? Where do you go from here?

Well, I actually write in more genres than I care to probably admit. In the last couple of years, I’ve really gotten into writing essays, short essays. Book reviewing. I have a novel, which is finished and I have an agent attempting to sell that for me. So I’ve written a novel, a 450-page, big novel. I don’t see any of the stories in this particular collection expanding into novels or anything else. But I do see myself writing more short stories. To me, short stories are a little experiment. It’s a way of testing out different points of view and tenses. A way to challenge yourself to tell a ghost story, tell a tall tale. I love the exercises in the back of John Gardner’s book, The Art of Fiction, where he lists all these assignments as a writer. So I’m slowly working through those. Right now, in the last few days, I’ve been working on poetry. I just did a really interesting community project. I partnered with a documentary filmmaker. We have this project here in Orlando that someone is spearheading to get all of these different artists together—choreographers, writers, dancers, musicians, visual artists—to ride all of the different lines of the Lynx bus system, which is our bus system here in the city. Orlando is really a driving city. It’s really the lower class who traditionally rides the bus, so the idea was a kind of ongoing ethnographic project. And, like I said, I was partnered with this filmmaker, and we rode the bus one day with the idea that all of these different artists would come off of their routes and write something inspired by their experience. I wrote two poems the other night. And I don’t write too much poetry, but I do write it. Usually when something sporadic or inspirational comes up like this. So, I’ll probably be working on a third poem this afternoon, to make a nice little grouping. But I see myself as mostly a fiction writer. I’m married to fiction, but I guess at times I’m very unfaithful to it.

For more information about and Vanessa’s latest news and appearances, please visit www.vanessablakeslee.com